A Jester in Jerusalem

(Published originally in the Jerusalem Post)

While recently wandering through the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, I looked into the book I had brought, and promptly burst out laughing. As my laughter echoed through that hushed and shadowy grandeur, a priest wrapped in pious thoughts frowned at me.

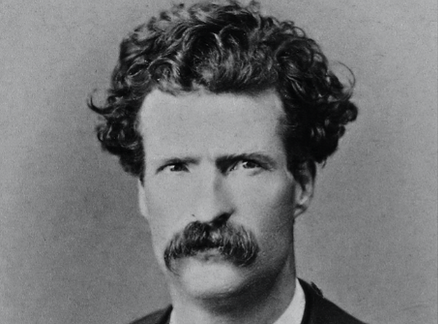

My mistake was opening Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad as a guidebook. This book, chronicling the pilgrimage and pleasure cruise of the ship, the Quaker City, through Europe and the Middle East, was a major step in transforming Mark Twain(the pen name and alter ego of Samuel Clemens) from a well-known frontier journalist to a writer of national stature.

Twain’s pithy quotes—there must be one for everything—still seem relevant, more than a century after his death. American comedians poking barbs at the French could do no better than listen to Twain, who labeled the French, in the Darwinian heyday, as the missing link between apes and men, and claimed that it was a wise Frenchman who knew his father.

His animated lampooning of European culture and aged layers of belief and tradition entertained his American audience in the post-Civil War boom of prosperity and national pride. As Twain mocks and mimics overblown, thoughtless piety, the mocking is so enjoyable because the mimicking is so admirable.

In the passage I read in the church of the Holy Sepulcher, Twain acts deeply moved when his guide highlights the weird “fact” that the tomb of Adam is there. “How touching it was, here in a land of strangers, far away from home, and friends, and all who cared for me, thus to discover the grave of a blood relation. True, a distant one, but still a relation…..The fountain of my filial affection was stirred to its profoundest depth, and I gave way to tumultuous emotion.”

During Twain’s long career, wide-ranging travels made many places his own: The Mississippi River, the pre-Civil-War South, the American West of stagecoaches and the Pony Express, San Francisco, California’s gold mines(the setting for his first great story, “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calveras County”), Nevada’s silver mines, medieval England, Hartford, Connecticut’s upper-class neighborhoods.

But his short, concentrated visit to Ottoman Palestine and Jerusalem, intended as the highlight of the pilgrimage, stands out in that the Old City which he walked through(it comprised almost the entire city then), to gather material for ongoing letters to several newspapers, really has changed very little. The shrines—The Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Dome of the Rock, the Western Wall, the Garden of Gethsemane, The Upper Room, the Via Dolorosa—are certainly the same as when Twain visited. Moreover, his richly textured word pictures convey as much to the modern tourist as they would to his contemporary reader. Almost 150 years have passed, but the dark, vaulted alleys, the scattered garbage, blended stenches, accosting merchants and beggars displaying children remain eternal. Only the politics, sovereignty and trinkets have changed.

Even Twain’s fellow travelers emanated a ludicrousness similar to that of a modern tour group with their cameras, folding chairs and orange kibbutz hats that look like thimbles on their heads. In Twain’s day the tourists’ uniforms included long white kerchiefs wrapped around their hats and trailing behind, and thick green spectacles with side glasses. They grasp “white umbrellas, lined with green… they are the very worst gang of horsemen on earth…bouncing high and out of turn, all along the line, knees well up and stiff, elbows flapping… and the long file of umbrellas popping convulsively up and down—when one sees this outrageous picture exposed to the light of day, he is amazed that the gods don’t get out their thunderbolts and destroy them off the face of the earth! I do—I wonder at it. I wouldn’t let any such caravan go through a country of mine.”

With such a group—but only eight from over seventy pilgrims—Twain left the Quaker City at Beirut to travel overland through the Holy Land by horse. They went first to Damascus, then south through Banias into Palestine, camping along the way. Twain reported several times on the emptiness and barrenness of the countryside, and on the contrast between his own earlier visions and the stark, small reality. “The word Palestine always brought to my mind a vague suggestion of a country as large as the United States. I do not know why, but such was the case. I suppose it was because I could not conceive of a small country having so large a history.”

By the time they approached Jerusalem through the Samarian hills, they anxiously sought their first view of “the venerable city”, which was, at least in a religious sense, touted as the highlight of their journey. But when they at last saw it gleaming in the sunlight, “white and domed and solid, massed together and hooped with high gray walls,” Twain was shocked by its smallness: “Why, it was no larger than an American village of four thousand inhabitants.”

Looking down today on the Old City from, let’s say, the Citadel tower near Jaffa Gate, one can see how precisely Twain captured the sense of the city when he wrote that a fast walker could walk around its walls in an hour, and that it “is as knobby with countless little domes as a prison door is with bolt-heads.”

Twain was one more in a long line of writers—Benjamin Disraeli, William Thackery, Gustav Flaubert, Nikolai Gogol, Herman Melville and others– who were pulled to Palestine in the nineteenth century. Almost unanimously, be they Catholic or Protestant, believing or skeptical, they pierced with their pens Jerusalem’s crust of piety. They expressed disdain, spiritual outrage, and even emotional trauma over the gap between their visions of a heavenly Jerusalem and the scummy, foul-smelling, dimly lit and all too humanly corrupt earthly Jerusalem. Melville found the church of the Holy Sepulcher “a sickening cheat.” Gogol felt insulted “to be deceived by Jerusalem.” Flaubert scorned the Holy city’s “hypocrisy, greed, falsification and lack of modesty,”(while also speculating on the city’s prostitutes).

But wry wit? Self-deprecating role-play combined with textured word-paintings and numerous biblical references(Twain special-ordered a Bible for his mother in Jerusalem)? Twain elevates scorn and skepticism to enjoyable, informational readability.

He duly accepts his guide’s story, on the Via Dolorosa, about St. Veronica’s handkerchief becoming imprinted with a portrait of Jesus after she wiped sweat from his face, “because we saw this handkerchief in a cathedral in Paris, in another in Spain, and in two others in Italy.”

Twain’s description of the Dome of the Rock(which he mistakenly refers to as the Mosque of Omar), with its “variegated marble walls and with windows and inscriptions of elaborate mosaic,” captures that shrine’s exquisite essence, and again absorbs the guide’s explanations with an innocent eagerness that could almost take a reader in. In the spot on the holy rock “where Mohammed stood he left his footprints in the solid stone. I should judge that he wore about eighteens.”

Twain, in a passage without a hint of sarcasm, admitted his youthful anti-Catholic bias, even while he praised the monks of a Judean Desert monastery for their hospitality. But his harsher, clearer bias against local Arabs oozed forth repeatedly, effusively and unapologetically.

Jews are subject not to excoriation but to omission. Though Twain mentions “the Jew’s place of Wailing”, and the legend of The Wandering Jew, which incorporates two thousand years of stereotyped images, Jews themselves don’t exist in his text: this, despite a Jewish majority in Jerusalem at that time, and the primarily Jewish expansion efforts outside the walls.

Another aspect of Jerusalem’s awakening also receives no mention. At the very moment Twain was laughing at Jerusalem’s old religious traditions, the first systematic and scientific surveys and excavations of that past were underway. The intrepid British military engineer, Charles Warren, was probing the outer parameters of King Herod’s Temple Mount, and usually stayed at the very hotel, The Mediterranean, that Twain’s party stayed at. They might have even overlapped. Now that would be interesting to imagine, the determined young researcher and curious young travel writer chatting over pipes and brandy in the lounge.

After an exhausting side-trip to the Dead Sea, Twain was happy and ready to leave Jerusalem. Like many a modern tourist he had had his fill of yapping guides, and shrines, and sights that “swarm about you at every step…It is a very relief to steal a walk of a hundred yards without a guide along to talk unceasingly about every stone you step upon and drag you back ages and ages to the day when it achieved celebrity.”

Twain’s party returned to the Quaker City at the port of Jaffa, and with relief he left this land of “dismal scenery.” It was a land he saw sitting “in sackcloth and ashes,” a desolate “dream-land” with no future..

The Innocents Abroad became the most popular travel book in American history. Shortly after its publication, Mark Twain found stability in marriage (he married the sister of a fellow passenger) and went on to write numerous books, including Huckleberry Finn, arguably the greatest American novel. He earned fame as a journalist, humorist, novelist, travel writer, lecturer and social critic, but not—fortunately—as a prophet.

By: Allan Rabinowitz